Products You May Like

For many people, the first stark-white patch that appears on their hands or face seems odd. As the patches begin to spread, a diagnosis of vitiligo—an autoimmune disease that causes about 1 in 100 people to lose their natural skin pigmentation, regardless of race or sex—is often inevitable.

“Vitiligo is characterized by white spots that result from the elimination of melanocytes by our own immune cells,” says Diane Madfes, M.D., FAAD, owner of Madfes Aesthetic Medical Center and an assistant professor of dermatology at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. “Most people develop symptoms before age 20.”

While vitiligo is not dangerous on its own, Madfes says it can be a marker for other conditions, including thyroid, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and lymphoma.

“We screen vitiligo patients with blood tests looking for abnormalities that are associated with the disease,” she says. “Unfortunately, some cases are idiopathic, which just means we don’t know the triggering cause yet.”

Treatable but Not Curable

While there is no cure, current treatment options include topical and oral steroids to decrease the inflammation that is attacking the melanocytes, phototherapy, and JAK inhibitors.

“Vitiligo can become dormant and burn itself out,” Madfes says. “And if the underlying problem is corrected, there is a good chance the patches will re-pigment. New discoveries, active research, and acceptance offer hope for patients.”

June 25 marks World Vitiligo Day, which the Vitiligo Research Foundation says serves not only to raise public awareness but also to shine the spotlight on the bullying, social neglect, and psychological trauma associated with the disease.

“The white patches can be socially debilitating for patients,” Madfes confirms. “We see an increase in depression with these patients.”

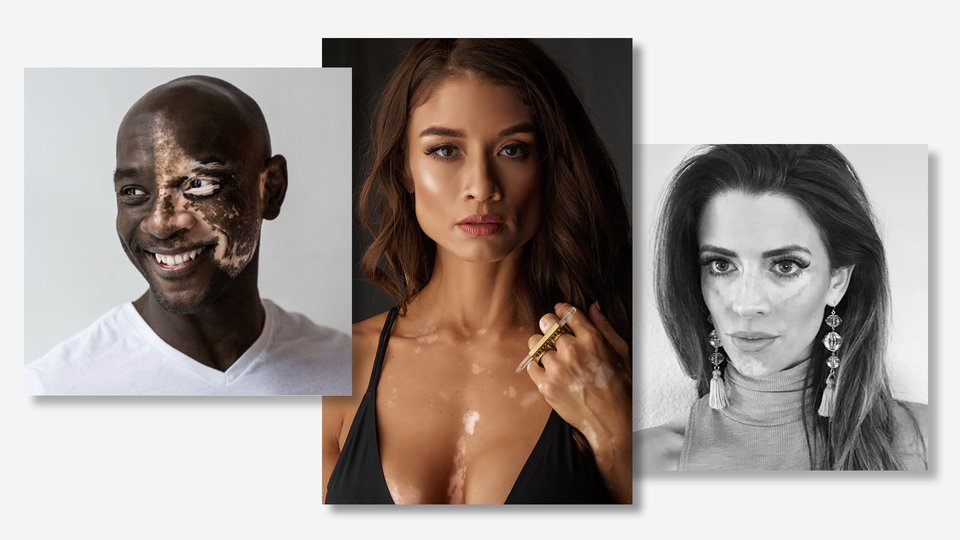

We interviewed three health, wellness, and fitness personalities who have vitiligo to learn more about their experiences.

The Personal Trainer: James McLeod

Growing up, James McLeod was afraid to look in the mirror—so he didn’t until age 7.

“Kids teased and bullied me,” he says regarding the segmental vitiligo across the left side of his face he’s had since he was 18 months old. “They called me a monster, the boogeyman, and would ask who erased half my face. Nobody even knew what vitiligo was in the early ’80s.”

One day, after his mother reassured him that he was beautiful, he decided to take a different approach to dealing with his classmates.

“I started going to school with a smile on my face and my head held high,” he recalls. “Eventually, kids stopped teasing me because I was just so happy. I began ‘collecting smiles’ from everyone I encountered and kept track of how many I received each day. It built up my self-esteem.”

Photo credit: Jitske Nap

Vitiligo wasn’t the only uphill battle McLeod faced: He lived in an urban area where drugs were everywhere and his father battled with addiction, leading him to spend time in jail and be absent from McLeod’s life. As a teenager, McLeod spent time in a youth detention center after getting caught selling drugs. Upon his release, he fell back into his old habits and ended up spending five years in federal prison. During this time, he realized that he needed to change his path in life.

“I was stressed, depressed, and overweight,” McLeod says. “So, I used my time in prison to educate myself. I read. I fell in love with working out. And, amazingly, I met some positive people, mentors who are still my best friends today.”

Once he returned home, McLeod earned his personal training certification and looked forward instead of backward. He now prides himself on shaping minds and bodies, demonstrating that your circumstances don’t define you, and using his positivity to help others.

“My mission in life is to help empower others to overcome their insecurities and fears no matter what they may be and help them become their best self,” he says.

McLeod will be a featured motivational speaker at this year’s virtual World Vitiligo Day event, sharing his experiences in overcoming adversity and learning to cope with his vitiligo and mental health.

“I went from selling dope to giving hope,” he says, adding that his “superpowers” are kindness, bravery, love, and inclusivity. “I’m the best dealer in America, giving out positive energy to the world.”

The Competitor and Model: Charisse Taylor

Before she’d even celebrated her sixth birthday, Charisse Taylor noticed a white spot on her ribcage. Next, both of her knees lost all their pigmentation. Her hands and feet followed. By age eight, Taylor had an official diagnosis: vitiligo.

“I felt ugly and ashamed,” she says. “Upon diagnosis, I was also told that there was no cure. So, I felt helpless, like I was forced to just accept it and adapt. But I’m grateful for that early life lesson: adaptation. It surely helped me along the way.”

Despite not feeling comfortable in her own skin, Taylor was recruited by modeling scouts as a preteen. Although she initially let her lack of self-confidence deter her from pursuing those opportunities, when she got into fitness competitions, modeling naturally followed. It was not without its challenges, however.

Photo credits: Dennis Cruz, David Bickley

“Any aesthetic blemish is a concern when you’re a model and your looks are what you are valued and hired on,” she says. “So, to this day, I still consider my vitiligo when going after gigs. I still assume that for any job where my body and aesthetics are going to be used to sell a product in any way, a standard commercial look is desired. But I don’t consider myself a victim. Letting go of the victim label and not allowing vitiligo to own me was an important step in achieving a healthy mindset.”

Today, Taylor’s vitiligo is spreading across her face, which she says may pose new obstacles in her modeling career. But she refuses to let it impede her spirit.

“I hold my head high,” she says. “I’m quite proud of the person I’ve grown to be. I’m loving. I’m understanding. But I’m also tough as nails!”

The Nutritionist: Breanne Rice

While getting ready to fly to Los Angeles for a modeling gig, then-19-year-old Breanne Rice noticed a small white patch beneath her left eye. She covered it up with makeup as best she could and assumed it would disappear on its own. Within months, however, it had spread in a mirroring effect around both of her eyes. A doctor’s visit confirmed it was vitiligo.

“I was completely devastated,” she says. “There was so much pressure already in the industry to look and be a certain way. It created so much insecurity in me that I wouldn’t even go outside without makeup on. I didn’t tell anyone except my parents.”

It took 10 years, but eventually, Rice grew tired of hiding her secret—which had by then spread to the bridge of her nose, her chin, her forehead, and the top of her lip. In 2016, she decided that if she didn’t stop seeing her vitiligo as a flaw and comparing herself to others, she would always struggle with feeling as if she wasn’t good enough.

“I posted a makeup-free selfie that happened to go viral, and sharing my story really helped me heal,” Rice says. “Putting yourself out there can be tough—especially in the public eye—but I have learned to love myself the way I am, and once you do that, it’s powerful. I hope to be one of the many voices to help others going through insecurity issues, to help them be strong and feel confident in who they are.”